Nature regards us without reference to language, colour or creed. Mt Tarawera’s 1886 eruption is in this way a cautionary tale. It reminds us to treat the natural world with respect and awe. To take nothing for granted, and to remember that we are in this life together, that we are here for each other.

What happened that June more than a century ago serves as a prediction as much as it records a moment in history. This is what nature did and what nature will do. We are not the first to reflect upon its significance.

Māori and Pakeha experienced the Tarawera eruption together. Both influenced the other’s understanding of what happened, and what it meant. We join them now, as we remember Amelia Haszard and Sophia Hinerangi; through their stories we consider the meaning of life and death, of humanity and the environment that shapes us. What does it mean that their lives were upended by the shaking of the solid ground, the very thing we choose as a metaphor for stability? There is in this a profound meditation and an opportunity to grow in our understanding of what is real and important.

The Pink Terraces, “Eighth Wonder of the World”

Pink and White Terraces

When William and Louisa Haszard left Canada in 1859, New Zealand was still a new land, the last place on earth settled by humans. They came to begin life afresh, as did the first Māori settlers who arrived some 500 years earlier.

For the Haszards’ daughter, Amelia, it was a place to lay a solid foundation for life as an educator and mother. To that end, she settled in Auckland and soon married her second cousin, Charles, a printer at the Daily Southern Cross newspaper. Amelia meanwhile worked as a teacher for the fledging Auckland Education Board in a school housed at St. Peter’s Church in Bombay. Soon, Charles donated his land for a permanent academy, still operating today as Bombay School.

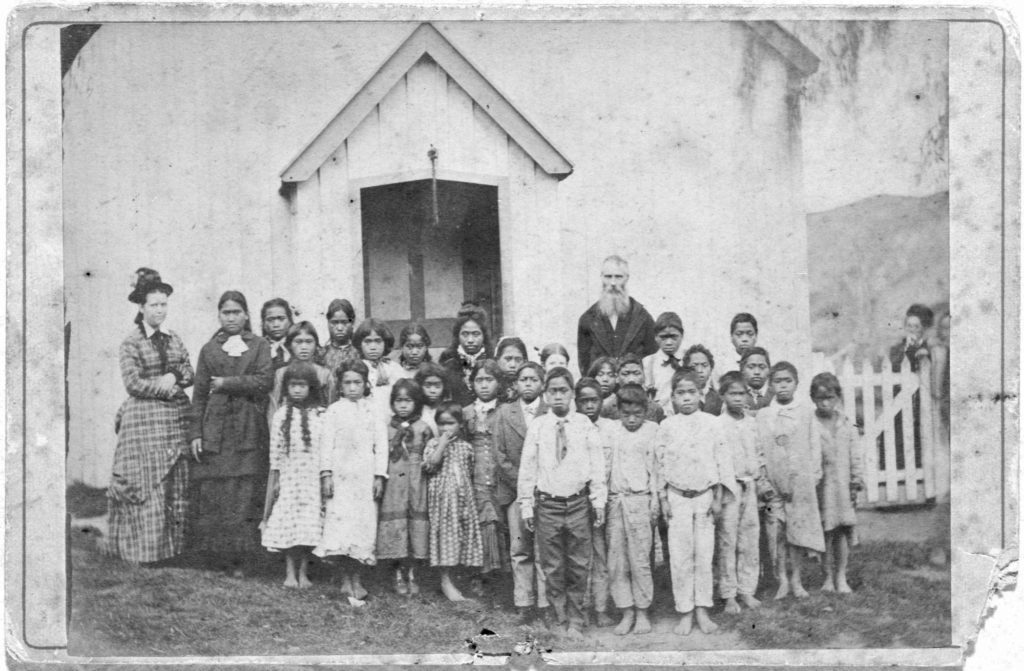

This was good work, but the Haszards felt called to something that was more pioneering. By 1880, the family had settled in Te Wairoa, gateway to Lake Tarawera and its famed sights. Charles and Amelia thrived there, looking forward to raising their growing family. As Charles became the headmaster of Te Wairoa’s school, Amelia worked tirelessly for her family while continuing to serve as a beloved teacher. The Haszards earned the respect and friendship of local Māori, and were known for their hospitality and kindness to all.

Amelia’s daughter Clara and Charles Haszard with students, Te Wairoa.

Te Wairoa

Te Wairoa was a fascinating place, built originally as envisioned by Samuel Marsden–a Māori township constructed according to the principles of English city planning, complete with a grid-like layout of streets and whare with fenced gardens.

Over time, the town evolved into an amalgam of traditional Māori and English elements. The largest building was McCrae’s Rotomahana Hotel, established to house the steady stream of foreign tourists who came to see the “eighth wonder of the world.” Needless to say, a full bar was one of the hotel’s enticing features, despite a vigorous temperance movement supported by the Baptist Haszards and Māori concerns about corrupting European influences.

Visitors to Te Wairoa came to see the world-famous White and Pink Terraces, along with the many geothermal wonders that surrounded Lakes Lake Rotomahana and Tarawera. Arriving at Te Wairoa’s outskirts, they first saw a welcome sign and then a board advertising the rates Māori guides charged for tours. The Tūhourangi managed the operation and provided guides.

Priced for the Rich

It was lucrative business with visitors the likes of the Duke of Edinburgh and famed English novelist Anthony Trollope, who wrote of his experience soaking in the cup-like terraces: “I can imagine nothing more delicious to the bather…. In the bath, when you strike your chest against it, it is soft to the touch. You press yourself against it, and it is smooth. Lie upon it, and though it is firm, it gives to you. You plunge against the sides, driving the water over your body, but you do not bruise yourself. I have never heard of other bathing like this in the world.”

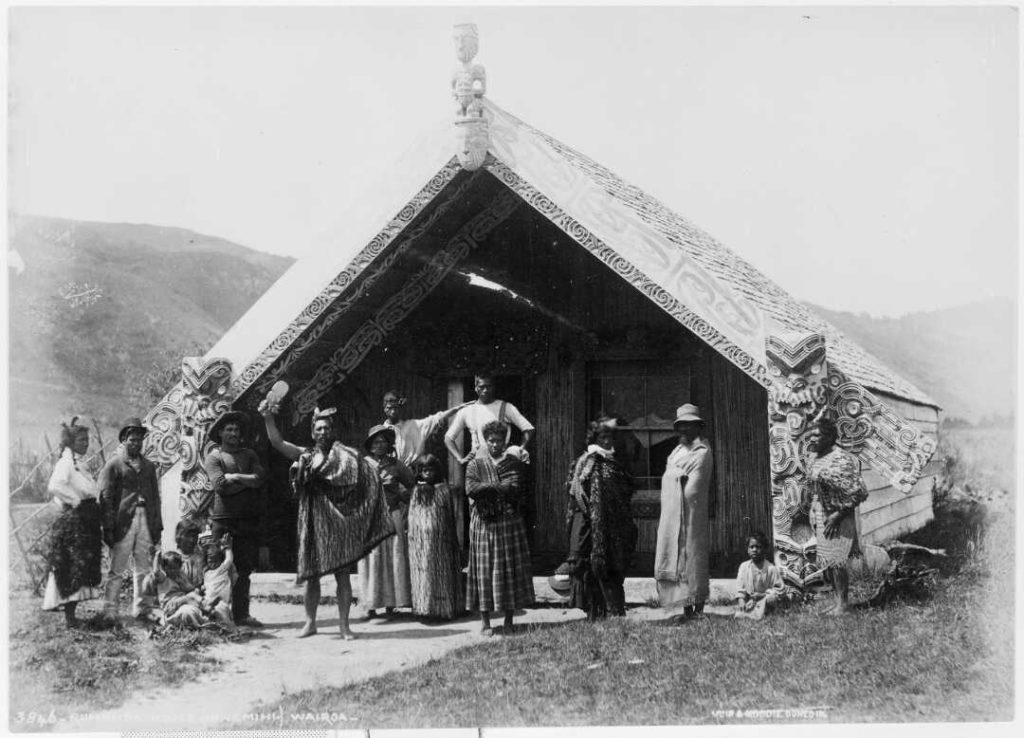

They paid a steep price for the experience too. Residents earned as much as 4,000 pounds per year, an astonishing sum, equal to 800,000 in today’s dollars. The deluxe package included seeing haka and performances of dancers at the wharenui, where the well-off residents decorated the eyes of traditional carvings with gold sovereigns instead of traditional pāua shells.

Hinemihi the Golden-Eyed Meeting House

Worries of Wealth and Grog

All this quickly became a matter of concern. Wealth and grog threatened to overwhelm traditional values and Māoritanga, provoking some in the community to predict a bad end to it all. Tūhoto Ariki, the elder priest of the community, spoke out against corruption and warned of the wrath of the ancestors. At the same time, the Haszards voiced their concerns as Baptist missionaries and leaders of the temperance movement.

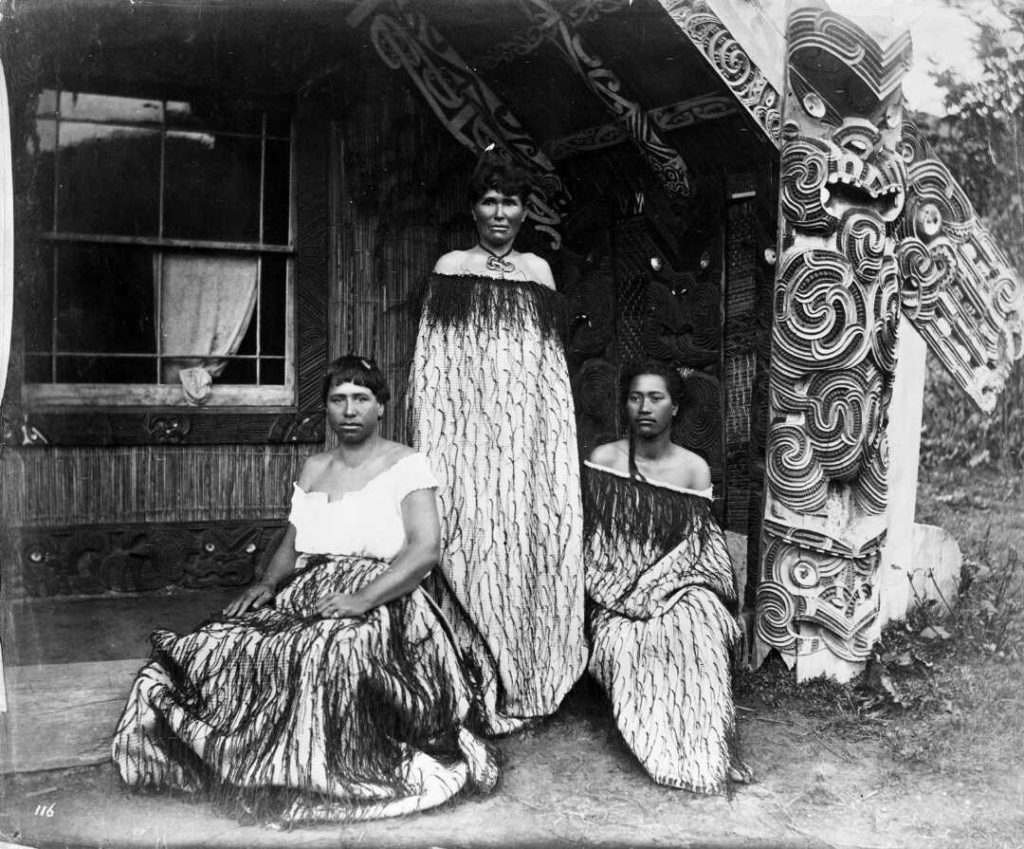

Those worries notwithstanding, the tourist trade continued full force. Generally, newcomers arranged with guides to travel by whaleboat and canoe to their coveted destinations. The most famous guide was Sophia Hinerangi, a highly-educated and masterful bi-lingual storyteller. She too was a Baptist and took the temperance pledge. Over a career spanning sixteen years, she led thousands of tourists across the waters to the terraces and guided them through their close-contact experiences with Māori culture. She was renowned and loved.

Then, in on May 31 1886, Sophia witnessed something that made her doubt if the good fortune would last. It was toward the end of the tourist season as she carried a small group across the lake, when an “eerie whimpering sound” unsettled the visitors as the lake waters suddenly rose and subsided.

“I pointed out to the Māoris who paddled the Canoe that the lake was higher than I had ever seen it,” remembers Sophia, “about 2 feet higher than usual; this made me apprehensive of some approaching calamity. We had not gone very far over the lake, before we saw another canoe paddling in the distance…several said they could see it.”

The Phantom Canoe, Painting by Kennet Watkins

Witnesses

Among passengers who witnessed it were Mrs Louise Sise, of Dunedin, and her husband and daughter, along with three other Māori women, six rowers, and three tourists from Auckland. “After sailing for some time we saw in the distance a large boat,” Mrs Sise wrote to her son. “It was full of Māoris, some standing up, and it was near enough for me to see the sun glittering on the paddles. The boat was hailed but returned no answer.” As a white steam cloud rose over Tarawera, Mrs Sise remembers Sophia saying, “I don’t think I shall see the Terraces again.”

Sophia recalled the sighting of the canoe as a clear omen. “As I looked earnestly at the men who paddled it, they turned into dogs and then the whole thing vanished. I said that was a Phantom Canoe, and a warning that something dreadful is going to happen.” Sophia felt a chill, “I thought of the chief, who had warned us that God would punish Wairoa for its wickedness.” (‘Turn into dogs’ is likely a reference to the kahu kurī cloak.)

Some ten days later, none could doubt the meaning of this disturbing sign.

Charles Blomfield, Mount Tarawera in Eruption

Eruption

Surveyor Henry Roche sat at a distance, witnessing the most powerful natural act of New Zealand’s human epoch. It started just after midnight on June 10. The eruptions continued for hours, not just from one peak, but ripping a ten-mile seam through the landscape over a period of hours. Most awful of all, the tear continued under the lake floor, causing the waters to boil and explode in a fury.

Camped at Te Puna-a-Tuhoe, Roche and his men at first felt an earthquake, then a sound like thunder, like that of an approaching tornado. Running outside and expecting a powerful storm, Roche was surprised to find a clear starry night, and calm winds. It was then he noticed a column of smoke in the distance, taking the form of a mushroom.

“All this smoke cloud was blazing with lightning, which scintillated through every part of it and, shooting out from its dark edges, fringed them with vivid light,” Roche wrote. “Continuous showers of red-hot scoria and great masses of rock, at white heat, were thrown up to a height of about 1,500 feet. The larger pieces were as big as houses, and at a distance of 16 miles were clearly visible from the time they left the crater until they reached their greatest height, turned and, having fallen, went bounding and thundering down the steep sides of the mountain….” He sums it all up: “The whole mountain appeared to crack open.”

What Science Says

Roche’s account finds corroboration in the analysis of modern scientists. “It started at Mount Tarawera, and it went northeast first and then it kind of turned around and went southwest and unzipped underneath the old Lake Rotomahana,” stated Cornel de Ronde, a New Zealand geologist who led the team searching for the lost Pink Terraces. “That’s when it turned most deadly. When the super-hot magma hit the cool lake water and water-saturated ground, it caused a massive steam explosion that opened a crater several times the size of the lake and hurled tons of lake-floor sediment for miles around. The whole lake was excavated, essentially, and all of that mud and debris splattered all the surrounding valleys…. For many, many years this land was completely uninhabitable. We’re not just talking a sprinkling of ash. We’re talking meters thick of mud.”

From within the village, the eruption presented itself as the sky falling.

Sophia at Hinemihi Meeting House

John Blythe’s Testimony

John Blythe, a houseguest of the Haszards, testified at the official inquest: “I was awakened about ten minutes to two by Miss Haszard asking if I felt the shock. The house was then shaking. We went on the veranda and saw immense volumes of smoke in the eastern direction, charged with what seemed to me to be electricity. The edge of cloud was framed with flame and the there was then a loud rumbling.”

The roof began to rattle. “There were shocks of earthquake every ten minutes….. Mr Haszard and myself kept walking to the windows to see if we could make out what the trouble was. It was very dark. We could see nothing but lightning. Then we felt that the door was being pressed out of shape, inwards, and we noticed some dirt at the bottom of it.”

With huge stones hitting the roof and ash piling up around the house, Blythe checked the time. “The last thing I remember was that there was an earthquake shock at half-past three. I am sure it was the time, as I looked at my watch. Without any warning, the roof fell in. The last I saw of Mr Haszard’s family, they were in the middle of the room.”

Henry Lundius Surveys the Scene

Surveyor Henry Lundius was also in the house. “We did not know at first what was going on outside, except continuous earthshakes and a terrific noise. Then came a fall of some solid matter on the roof. One extra-large lump penetrated the iron on the roof and went through a picture hanging on the wall. I was standing at the window all the time trying to see what was going on outside, but I could see nothing. The darkness was so great that one could feel it. Miss Haszard – Clara, the eldest daughter – was sitting at the harmonium playing and singing hymns. I saw her get up and stoop to look at the bottom of the door, when a cracking noise was heard and I found that the roof had collapsed.”

Under the wreckage lay Blythe, Lundius and Clara. Blythe heard Lundius call out. “Who is there?” He was in the corner with Miss Haszard. “Keep off from me, I have the windows,” he shouted, warning Blyth and Clara that he would try to break through the window.

“Then I heard glass splinters,” Blythe continues, “he then said he could not do to with his hand, but would kick it out with his foot, which he did. During this time I found Miss Haszard alongside of me. The ceiling was pressing on my head and shoulders so that I could not stand upright. Mr Lundius dropped Miss Haszard off the broken sash. I called out to him not to forget me. He gave me his hand and pulled me through the sash, and asked if I was hurt. I said ‘No; make for the old house.’“

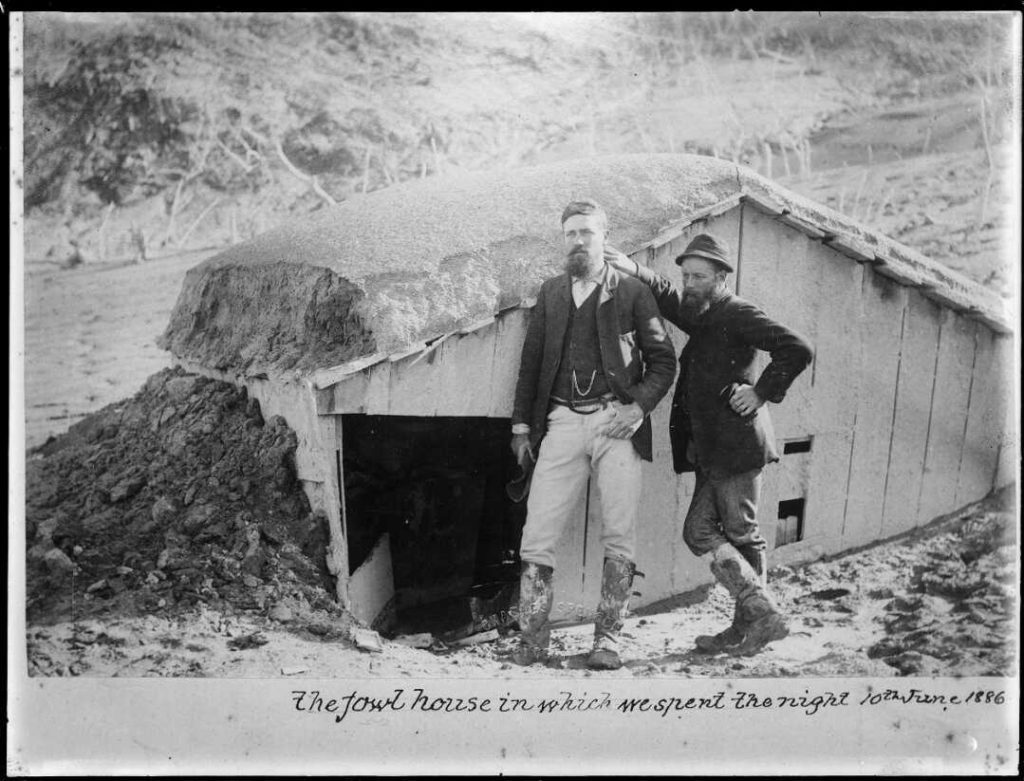

Blythe and Lundius outside the fowl house after the eruption

Escape

As their dwelling took fire, the trio escaped. “I ran outside…and took refuge in the fowl-house, and stayed until the morning, when I was joined by Mr McRae and others. We looked and listened at the windows, but could hear nothing. The wall was standing, but the roof had fallen in. We took the girls to Sophia’s whare.”

Lundius and Clara were with him. “I was beyond being frightened,” Lundius recalls, “All I hoped for was that the end would come quickly.”

About nine o’clock in the morning Joe McRae appeared. He was owner of Te Wairoa’s popular tourist hotel.

“We all went up to the ruins,” Lundius later recorded, “and found Miss Ina Haszard and old Mary sheltering under some furniture in what had been my bedroom. We soon got them out and the two sisters – Ina and Clara – were once more together. We did not hear a sound or indication of anyone else being alive under the debris.

“But as they began to clear away the debris of the demolished house”, Lundius writes, “we saw a hand move up through an opening made by the digging, and found Mrs. Haszard alive. We soon got her out. One of her legs was badly crushed…. We improvised a stretcher and started to carry her out.“

Amelia Haszard Tells the Story

Her memory of the night remains astonishing to read:

“My two daughters escaped into a detached portion of the house. While sitting in my chair with my three remaining children around, I was pinned to the floor by the roof falling in….and I believe that it was at that time my husband was killed. I had my youngest child, a girl aged four, in my arms, my boy aged ten on my right and my little girl of six on my left.”

As the weight of accumulating ash and mud pressed increasingly hard on her, Amelia struggled to shelter her children. “The child in my arms called for me to give her more room as I was pressed against a beam, but the load of volcanic mud pouring down me prevented me from being able to render any assistance, and the child was crushed and smothered in my arms and died.”

Amelia remembers her son’s last words, too. “The boy said, ‘M’amma, I will die with you,’ and I think, he died shortly after, as he did not answer again. The little girl, I think, died shortly after, as she said, ‘Oh, my head,’ as the mud was beating down on her, and she spoke no more.”

The Rescue

Blythe recalls the moment they uncovered here. “We partly removed the roof, and got at her hand. She was quite conscious and knew me. There were two children with her. She was in an armchair, which had fallen up against the chiffonier. On her lap little Mona was lying dead, and Adolphus to the left, close to her dress. She was got out and carried to Sophia’s whare.”

When Charles Haszard was finally uncovered, he lay with his skull shattered nearby.

McRae’s hotel was no better off. Crushed by hot rocks, ash and mud, its survivors staggered to Sophia’s whare around 4 A.M., with rugs and blankets over their heads as protection against the bombardment of mud and rocks. Sophia’s husband reportedly shouted, “Haere mai, e Tai, kei te wera te ao” – “Come and see, the world is going to be burnt!” They sheltered some 62 people in their home, its traditional high-pitched design and solid beam walls giving the protection that other buildings could not. It was one of the few places to survive intact.

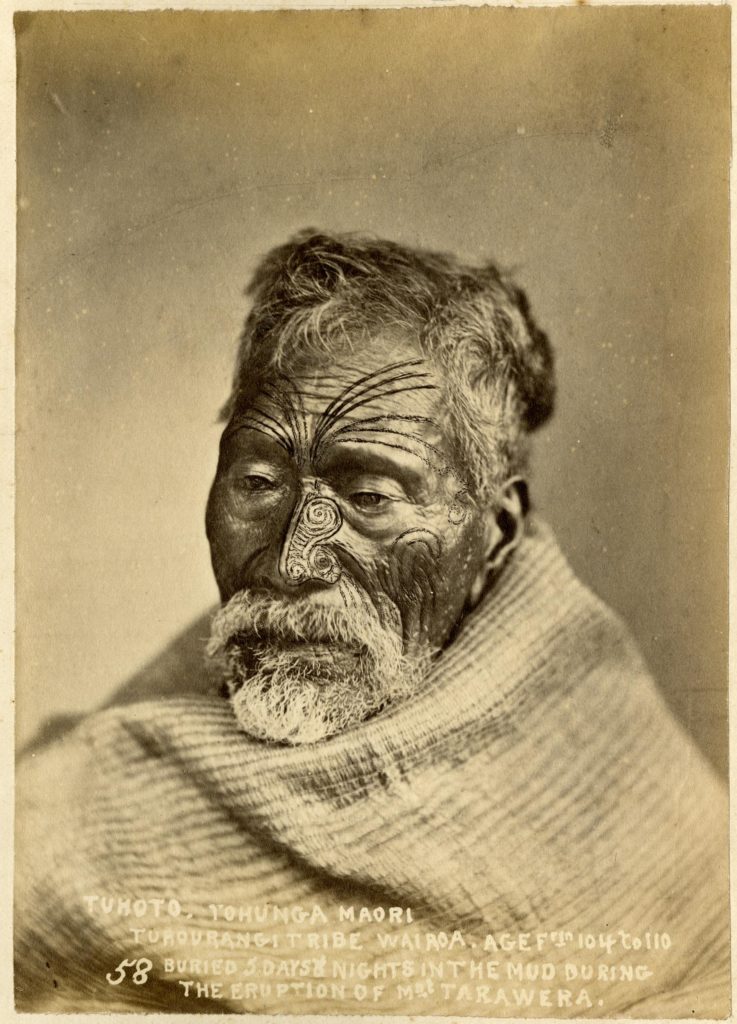

Tūhoto Ariki

The Prophet

Meanwhile, hundred-year-old Tūhoto Ariki found himself in the spirit world, buried beneath a meter of mud.

He had lived in solitude at Te Wairoa, feared and respected as a powerful tōhunga.

Tarawera’s tourism industry had worried Tūhoto. His kinfolk’s behaviour and exploitation of their heritage was sure to anger the unseen world. Tūhoto had no doubt as to the meaning of the waka wairua—phantom canoe. “He tohu tēnei, arā kia horo tātau i tēnei takiwā” – “it is an omen, a sign and a warning that all this region will be swallowed up.”

Historian James Cowan and Māui Pōmare, record this Māori lament about Tūhoto. “Tūhoto the last of the great magicians and wonder-workers of the Araki. Here he was dug out by the rescue party after the eruption of Tarawera, when Wairoa was buried deep under mud and stones and when a hundred of Tūhourangi perished beneath that volcanic rain—truly the rain of the gods. For it was Tūhoto’s ancestor, the Atua who sent that awful rain to punish and destroy the people of the Wairoa.”

The authors explain that this ancestor, Tamaohoi, was the atua, of the mountain, whom Tūhoto invoked. Tamaohoi was the first inhabitant of Tarawera and chief of the tangata-whenua, the primal ancestors of all who live in New Zealand. A vicious cannibal, Tamaohoi was especially interested in assailing and eating passing travellers—not auspicious for a local economy based on tourism.

Warnings

Tūhoto did all he could to warn the people of Te Wairoa. And after the tumult, he lay in peace for four days and nights. Cowan records that, “He said he was in the Rēinga, the spirit world, when the digging party let daylight into his volcanic tomb. The ancient pagan did not seem particularly pleased at being disturbed; as for the Maoris, they were disgusted at his resurrection. ‘Why didn’t you leave him there?’ they asked the searchers, and they suggested that the best thing that could be done with the dangerous old wizard was to cover him up again.”

Tūhoto wasn’t alone in warning the affluently comfortable residents of Te Wairoa of the tenuous thread that supported them. Science too had a warning, which as it often does, supports that of mystics and meditators.

In 1859, renowned geologist Christian Gottlieb Ferdinand Hochstetter made a prediction, reported in New Zealand newspapers: “I am of the opinion that this whole portion of the mountain up to the Te Kopiha fountain—being, as it seems, thoroughly decomposed by hot vapours—will some day cause a sudden catastrophe by falling in, and covering the Ratoreka plain with a flood of hot mud.”

And so it did. Wiping out Te Wairoa, making it uninhabitable and sterile for decades.

Haszard home and family before and after the eruption

Haszard home after the eruption

Meaning in Tragedy

What to make of all this? The options for interpretation range from the wrath of a god to the randomness of geology. But the meaning is perhaps best found in the relationships. After the cataclysm, the survivors found themselves sheltering in a single house, Sophia’s whare. The mountain didn’t affect people differently based on ethnicity or culture, and all had to contemplate the same questions concerning what was valuable and worthless, what they’d done right and what they’d done wrong, and what might be gained by listening to shunned voices of the spiritually inclined—in this case the tōhunga Tūhoto and the teetotaling Baptist missionary, Charles Haszard.

For that matter, what of the warning of a Hochstetter, a god-fearing scientist, whose voice was drowned out by more pressing concerns of commerce? True, nature’s movements are not driven by angry divine decree. But neither is our relationship to nature random. Our approach to the environment and to each other is something we plan, and whether we do so with respect and understanding has everything to do with our fate. All this and more is here for us to consider in the saga of Tarawera.

The residents who survived had little left but their lives. The land was barren for decades. With 125 of the 150-strong Tūhourangi living in the region dead, the survivors dispersed, moving to nearby Whakarewarewa, where Sophia continued to work as a guide, recruiting and training women to work in the business. Mrs Haszard died a widow, having lost her husband and three children in the conflagration.

The Children

Mona age 4

Edna age 6

Adolphus with Amelia

VISIT AMELIA

GEOLOCATION OF AMELIA’S GRAVE SITE AT PUREWA – CLICK FOR DRIVING AND WALKING GUIDANCE

CREDITS:

Pink Terraces: Alexander Turnbull Library, 025-017, Heaphy, Charles

Haszards with students: https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/62541/

Hinemihi meeting house: Alexander Turnbull Library, Collection: PA7-19-19: Burton Brothers, 1868-1898

Sophia at Hinemihi: Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/2-029217-F, Sophia Hinerangi, Kate Middlemass (Kati), and another guide, outside Hinemihi meeting house, Te Wairoa

Kennett_Watkins, The Phantom Canoe: A_Legend_of_Lake_Tarawera, Google Art Project: Auckland Art Gallery, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Mount Tarawera in Eruption: Charles Blomfield, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Blythe and Lundius Fowl House: Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/1-023412-G

Tuhoto Ariki: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) © The Trustees of the British Museum

Haszard House and family: Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/2-002514-F

House after eruption: Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/2-002515-F

Mona Haszard: Alexander Turnbull Library, PA2-2529

Edna Haszard: Alexander Turnbull Library, PA2-2530

Adolphus and Amelia Haszard: Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/2-002514-F (CROPPED)

Charles Haszard: Alexander Turnbull Library, PA2-2526

Amelia Haszard: Auckland Libraries, 797-A16205, Elva Shepherd Collection

References:

Bombay School: https://www.bombay.school.nz/158/pages/24-opening-of-bombay-school

Te Wairoa, The Buried Village: A Summary of Recent Research and Excavations Author(s): ALEXY SIMMONS, Source: Australian Journal of Historical Archaeology , 1991, Vol. 9 (1991), pp. 56-62 Published by: Australasian Society for Historical Archaeology https://www.jstor.org/stable/29543289

General sources: https://www.rotoruamuseum.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Tarawera-Digital-Resource.pdf

https://www.totallytarawera.com/about-us/our-history/

Roche, Henry, 1856-1949 : Volcanic eruption at Tarawera and Rotomahana as seen from the Puna-atua-hoe Railway survey camp about two miles from Ohinemutu

whoi.edu/oceanus/feature/in-search-of-the-pink-and-white-terraces/

Written accounts and further reading:

Lundius account: nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-Gov10\_04Rail-t1-body-d8-d1.html

Hochstetter report: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/OW18860702.2.109 Hochstetter

Keam, R.F. (2004). Dissolving Dream: The improbable story of the first Baptist Maori mission. Auckland, NZ: R.F. Keam. p. 99

Paul Diamond. “Te tāpoi Māori – Māori tourism – 20th-century Māori tourism”. Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

www.wikiwand.com/en/Sophia\_Hinerangi